Welcome to “Around the World.”

This page opened when my colleague and friend Dave Bartholomae and his wife Joyce shared with me some exceptional ex votos they saw in their travels. I have posted them here (they appear at the end of this page). I hope more friends, as well as people I don’t know, will do the same with both ex votos and immaginette, sharing with me images I will dutifully post, as well as comments, suggestions, and stories, especially stories about the meaning and the relevance of these humble religious artifacts in their lives.

To add your post, please click here and fill out the form on my “Around the World” submissions page.

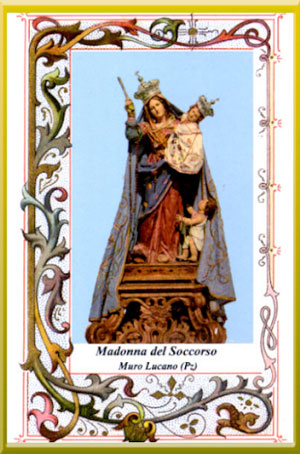

Vi Racconto la Mia Madonna del Soccorso

Maria Giovanna Negrone Casciano | “Vi Racconto la Mia Madonna del Soccorso”

“Salve, rispondo qui al suo post (omettiamo dove: n.d.A.) pubblicato sulla pagina dell’unitre di Muro Lucano. Non è più possibile votare. Il censimento del FAI si è concluso da alcuni mesi. La chiesa della Madonna del Soccorso si è classificata 3° in Basilicata e 115° a livello nazionale, su circa 40mila luoghi / siti di interesse che hanno partecipato. Avendo superato le 3000 firme, la nostra chiesa è diventata ufficialmente un “luogo del cuore FAI” Grazie per aver condiviso con noi la sua storia personale …”

“Salve, rispondo qui al suo post (omettiamo dove: n.d.A.) pubblicato sulla pagina dell’unitre di Muro Lucano. Non è più possibile votare. Il censimento del FAI si è concluso da alcuni mesi. La chiesa della Madonna del Soccorso si è classificata 3° in Basilicata e 115° a livello nazionale, su circa 40mila luoghi / siti di interesse che hanno partecipato. Avendo superato le 3000 firme, la nostra chiesa è diventata ufficialmente un “luogo del cuore FAI” Grazie per aver condiviso con noi la sua storia personale …”

Autrice del messaggio è la dott.ssa Chiara PONTE; oggetto? La chiesa del Soccorso in Muro Lucano …

Il mio nome è contemporaneamente un omaggio alla Madonna del Soccorso (o Madonna della Neve) e nonna Giovanna.

Essendo nata il 5 Agosto, giorno dedicato alla Vergine col titolo citato, ma anche Dedicazione della Basilica di santa Maria Maggiore in Roma, mamma chiese alla suocera la possibilità di abbinare il suo nome a quello della Madonna perché a Muro Lucano, suo paese natìo, vi era questa chiesetta. Nonna rispose semplicemente: “Figlia mia, prima il nome della Madonna e poi il mio …”.

Non mi chiedete perché e per come ho desiderato all’improvviso riscoprire la mia Madonna; mi viene solo da pensare che ogni cosa accade a suo tempo, e comunque il fatto che questa immagine ritrae la Vergine con lo scettro in mano nell’intento di scacciare il demonio (attenzione anche al bambino, in basso a destra guardando la statua) evidenzia l’affidamento a Lei da parte dei miei genitori: l’aver ricevuto il Battesimo nel giorno dell’Assunzione comprova ciò.

Nel positivo di tutta questa storia c’entra anche nonna Carmela, con la sua inseparabile corona del rosario! A lei, a donna Concetta Sisto de Divitiis, a don Francesco Parrella, la mia infinita riconoscenza per l’indubbio valore della loro presenza nei miei primi anni di vita.

La Chiesa del Soccorso, ci riferiamo sempre a quella di Muro Lucano, è stata riaperta nel 2008; in precedenza, la statua era custodita nella Chiesa di san Marco, dove è avvenuto il furto anche dello scettro della Vergine, dell’antico mantello che indossava, dei gioielli ex voto …

Ho appreso ciò dalla dott.ssa Chiara PONTE, la quale ha comunicato quanto segue: “(…) Vorrei precisare che del mantello e degli ex voto si sono perse le tracce dopo il terremoto del 1980, mentre i due bambini e credo anche il bastone (il riferimento dovrebbe essere allo scettro della Madonna, n.d.A), sono stati rubati nella chiesa di San Marco, dove la statua è stata ospitata per alcuni anni, in attesa della riapertura al culto, nel 2008, della chiesa della Madonna del Soccorso (danneggiata dal sisma del 1980)”.

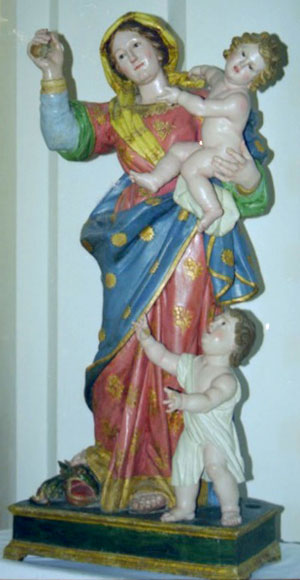

E’ la stessa Statua, senza gli abiti delle Solennità; possiamo, tuttavia, considerare storica questa foto a motivo dei furti sopra descritti.

Dal 5 Agosto 2021, celebrazione dei 400 anni dalla fondazione della chiesa di santa Maria del Soccorso in Muro Lucano, l’immagine della Vergine è questa.

Sui beni inventariati e trasferiti alla Sovrintendenza (Potenza, Matera o entrambe?) è noto un PDF del 1982, realizzato dal Ministero per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali (riporto fedelmente il frontespizio del Documento in questione) e riguarda il patrimonio storico-artistico della Basilicata. Per chi gradisce sfogliarlo -è comunque disponibile online – segnalo a pagina 67 l’indicazione esatta dei beni presenti nella Chiesa di santa Maria del Soccorso a Muro Lucano, inventariati e trasferiti alla Sovrintendenza: “(…) 6 sculture !ignee, 1 base processionale e 1 pastorale”.

Per quanto attiene al titolo “Madonna del Soccorso”, rinvio a questo interessante studio | LINK

Nel caso specifico della Vergine onorata a Muro Lucano, credo ci sia ancora confusione -nelle Schede artistiche censite in collaborazione tra il Ministero dei Beni Culturali e la Chiesa Cattolica- tra il fanciullo descritto in dette Schede e il bambino a destra della statua (ovviamente prima dei menzionati furti).

Il 29 Agosto u.s. mi sono premurata di segnalare la svista nei seguenti termini: “non è un fanciullo ma un bambino il soggetto di cui al seguente link | LINK

D’altro canto, non mi pare s’intraveda un fanciullo neppure sull’affresco presente nella volta della stessa Chiesa: è ancora un bambino il destinatario della protezione della Vergine!

Tra storia e cronaca … restano aperte altre piste da battere: quella, ad esempio, dei furti. Chi è perché ha rubato lo scettro della Vergine; le Corone della Vergine e del Bambino, oltre alle statue dei bambini (il Bambin Gesù in braccio a Sua Madre, il bambino presente in basso a destra della statua, semi nascosto dal mantello della Vergine)?

Come è potuto accadere che, dopo il sisma del 23 Novembre 1980, si siano perse le tracce dell’antico mantello della Vergine e degli ex voto?

Cercheremo e attenderemo risposte.

Non posso chiudere queste riflessioni senza citare Satana, l’Avversario per eccellenza.

Al riguardo, il libro più originale da me letto è L’Invidia di Satàn, scritto dal Teologo don Marco Pozza, parroco del Carcere di massima sicurezza “Due Palazzi” a Padova.

Ripensando alla mia vita, alla storia sofferta della mia famiglia, al Male con cui mi sono confrontata vis à vis non posso che dire Grazie! alla mia Madonna del Soccorso.

Grazie! per avermi protetta in questi lunghi anni.

Davvero ho potuto contare soltanto sul semplice: Ricòrdati! cui mamma – quando era in vita – mi richiamava costantemente, ossia il pensiero alla bella Vergine, come lei definiva Maria. Eppure, intorno ai 7/8 anni, affermavo che Maria è proprio brutto come nome; che da grande sarei andata al Comune per farlo cancellare; che mi dovevano chiamare tutti Giovanna. Ovviamente, nessuno mi dava retta …

Ho ben presenti anche le belle risate di papà, della serie: “Padre, perdonala perché non sa quel che dice …” e il discorso non proseguiva oltre …

A motivo di tutto questo, spero di tornare a Muro Lucano nella prossima Estate per riconoscere, in quella chiesetta che mi ha ospitato bambina, le anticipazioni di tutto il Bene che la Provvidenza, nel tempo, mi avrebbe donato.

Questo articolo avrà due dediche speciali, poste sullo stesso piano: a una bambina per la quale abbiamo pregato insieme a don Marco durante la Novena ai santi Anna e Gioacchino; a Emma e Ginevra, le nipotine di don Marco, nate oggi, 24 Settembre 2021.

Nel ringraziare la dott.ssa Chiara Ponte per tutta la collaborazione e l’aiuto che mi ha offerto nel soddisfare ogni mia curiosità; il dr. Antonio Mennonna, nipote di S.E. Antonio Rosario Mennonna, per avermi fornito la Novena alla nostra Madonna del Soccorso; la prof.ssa Mariolina Rizzi Salvatori per aver desiderato ospitare un mio contributo sul suo sito; don Marco Pozza per la costante ed eccezionale testimonianza in difesa della Verità e del Bene; desidero idealmente riportare lo scettro tra le mani della nostra Madonna lasciando la parola a don Marco: “Dio le ha messo tra le mani lo scettro del comando per imperare su tutto: vuole che i suoi figli, attraverso la Madre, tornino a essere belli come Lui li aveva creati. Non sovrappeso, come Satàn li ha ridotti. Ogni regina, per il fatto d’essere tale, è di una bellezza impareggiabile, sopraffine, invidiabile: quella di Maria, però, è il non plus ultra. Immaginarla è scottarsi, cercare d’imitarla è inorgorglirsi, chiamarsela appresso è sentirsi figli d’una Madre ch’è la meraviglia di Dio. Il capolavoro dei capolavori”.

E’ possibile visionare un breve filmato della Festa celebrata il 5 Agosto 1968 al seguente link | LINK

Unitre Muro Lucano cfr.| LINK

TG7 Basilicata | LINK

Le cronache lucane, cfr. | LINK

La chiesa di santa Maria de Soccorso nelle Schede C.E.I. | LINK

M. Pozza, L’invidia di Satàn, Edizioni San Paolo 2021, Per conoscere la missione di don Marco, segnalo il suo sito | LINK

I filmati dell’intera Novena 2021 ai santi Anna e Gioacchino sono presenti su youtube; indicativamente, inseriamo il primo giorno | LINK

Cfr. | LINK

La Novena alla Madonna del Soccorso venerata in Muro Lucano (PZ) può essere scaricata al seguente link | LINK

M. Pozza, L’invidia di Satàn, op. cit., p. 160.

Ria Brodell: Devotion

EXHIBITION || Ria Brodell: Devotion

The Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Rollins College, Winter Park, FL

|

DEFINITION OF DEVOTION FROM MERRIAM-WEBSTER’S DICTIONARY

1. religious fervor, piety; an act of prayer or private worship Ria Brodell (b. 1977) disrupts traditional narratives and offers multifaceted ways to experience the concept of devotion. While Brodell’s art stems from personal experience, the works in this exhibition allow for a nuanced rumination on gender and sexuality from both historical and contemporary contexts. The exhibition includes works from the artist’s series, Butch Heroes and The Handsome & The Holy. Butch Heroes presents highly detailed paintings of historical subjects who challenged gender norms. The paintings incorporate the structure of Catholic prayer cards; the artist’s aesthetic approach is deeply informed by a Catholic upbringing. These meticulous paintings are accompanied by scholarly documentation of the subjects portrayed. In explaining the motivations of an earlier series, The Handsome & The Holy, the artist writes, “I am interested in the play between queer desire and the construction of gender identity as seen alongside my religious upbringing. This series of work attempts to catalog the influential, yet seemingly paradoxical, figures in my personal history.” Featuring new and recent work by Brodell, this exhibition recontextualizes devotional imagery in the permanent collection of the Cornell Fine Arts Museum. Most significantly, Ria Brodell: Devotion allows for complex readings of gender in historic terms and through a religious framework. This exhibition marks the artist’s first solo presentation at a museum. – Text from booklet published by Cornell Fine Arts Museum |

|

From the Travels of David Bartholomae

From David Bartholomae –

We just did another piece of the Camino de Santiago and ended up in Astorga, which has one of the pilgrimage route’s lovely small cathedrals. This one had an ex voto.

We just did another piece of the Camino de Santiago and ended up in Astorga, which has one of the pilgrimage route’s lovely small cathedrals. This one had an ex voto.

The panel below the painting tells the story of the collapse of scaffolding as the cathedral was being built. With the intervention of St. James (Santiago), the men were saved.

From Mariolina Salvatori –

I so admire you for your persistence on this wonderful pilgrimage.

Thanks for thinking of me. I am glad ex votos and prayer cards bring me to mind. I wonder how those who do not know about ex votos read this painting. And I need to think about how the presence and monumental size of this ex voto, and the fact that it is displayed next to the main altar, and that it was obviously commissioned to a reputable painter, impact the tradition of the ex voto. In this case it is not the humble person, but the Cathedral itself that was in peril …

From David Bartholomae –

So, you prompted me to do my homework. We couldn’t get close enough to the text to be able to read it when we were in the cathedral. (see Bernardo Velado Graña, “Juan De Peñalosa y Sandoval: Un pintor cordobes en la cathedral de astorga”)

The painter is Juan de Peñalosa, a painter of some significance who did other paintings in the cathedral (and across Spain) and who also worked on the new baroque retable. He also painted the other images in this chapel. The painting dates from somewhere between 1616 and 1623. The event dates from 1436. The story is that two workmen fell into a well and were saved by an intervention from “the majestic virgin” (la virgin de majestad). (If you were to address the King, you would address him as “majestad.”)

The painter is Juan de Peñalosa, a painter of some significance who did other paintings in the cathedral (and across Spain) and who also worked on the new baroque retable. He also painted the other images in this chapel. The painting dates from somewhere between 1616 and 1623. The event dates from 1436. The story is that two workmen fell into a well and were saved by an intervention from “the majestic virgin” (la virgin de majestad). (If you were to address the King, you would address him as “majestad.”)

And you are right about the odd point of focus in the painting. The miracle is represented in the lower right corner and the virgin is a tiny figure in the upper right corner. The focus is on the long parade of bishops, monks, priests and noblemen to celebrate the saving of the men (el Cabildo Catedral) — it is their clerical power that is celebrated, particularly Bishop Messia de Tovar, who wears the “capa magna.” The painter is also in the painting (I’m not sure which figure) — he is, the article says, looking out at us. There are also some shepherds with their dogs, a reminder of our salvation.

The painting is highly valued now because it shows the old city walls and the work that was being done on the old Romanesque cathedral in the 17th century. They were refashioning the building in gothic style — the façade is now a highly elaborated rococo, which does not appeal to my sensibilities! The tower, for instance, is gone and replaced by two towers.

– Exchange between David Bartholomae and Mariolina Salvatori

From Biagio Gamba, Esquire

Collector and Scholar of Immaginette, Santini, Small Devotional Images

“Spiritual” Antidotes against the Plague

In the Middle Ages, the plague wiped out almost one half of the European population. The epidemic broke loose in the Orient, and spread throughout Europe, carried on board ships which from the port of Caffa (Crimea) reached Constantinople (first to be hit by it) and from there sailed to Genova, from which it spread to the center of Italy, and to Messina, from which it crept up the peninsula as far as Rome. But, as it is well-known, the plague hit all of Europe.

Physicians were absolutely inadequate and unprepared to deal with this terrifying disease. At that time, medicine relied on “other kinds of knowledge,” Astrology in particular. In the event of an epidemic, they would recommend:

1. Serenity of spirit

2. Sobriety

3. Healthy foods

4. Distance from contagion

5. To wear wools and minerals

6. To trust the attendant physician

7. Use of uncontaminated objects

8. Prayers, to be well assisted

9. Resignation to the will of God

These remedies were considered to be effective in the case of “invincible” diseases, like the plague, or cholera. Alongside practices which even today we could consider somewhat valid (#3, #4, #6, #7), most advices were of spiritual nature.

In March 1547 the plague was spreading in the town of Trento, seat of the famous Council. The Council Fathers decided to suspend work and to transfer to Bologna. It’s said that they were saved from contagion thanks to a particular exorcism, reciting a short prayer, used since the Middle Ages.

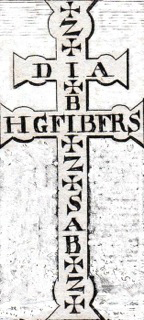

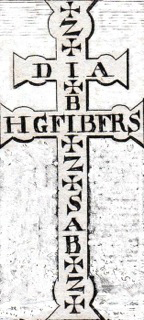

The formula had been inserted in a particular cross, Cross of Saint Zaccaria, Bishop of Jerusalem (see images of Cross).

The formula had been inserted in a particular cross, Cross of Saint Zaccaria, Bishop of Jerusalem (see images of Cross).

The letters, which were to receive a special blessing, had to be “worn” (through a medal, a small image, a relic) with sincere devotion, in time of plague. According to legend, the Saint himself would have been written them on a sheet of parchment paper, later recovered in the Monastery of Frayles in Spain.

Here are some of the prayer’s invocations (translated from Latin by Gamba). Each invocation begins with one of the letters transcribed on the cross.

Cross of Christ save me

Zeal of your home free me

The Cross wins, the Cross reigns, the Cross governs, through the sign of the Cross save me, Lord, from this plague

God, my God, chase the plague away from me, from this place, and save me

In your hands, Lord, I place my spirit, my heart, and my body

God was before Heaven and Earth and He can therefore save me from this plague

Who wrote this prayer is not known for sure. There are some references to the Sacred Scriptures and to the Psalms, in particular. In part, it is an example of invocation of vernacular nature often found in syncretistic rituals (See Gamba’s “Gli Agathazettel e il rito del fuoco” and “Quando i devoti mangiavano i santini” at www.biagiogamba.it)

But we know for sure that prayers were more efficacious if accompanied by a Saint’s intercession. In this case, there were Protectors against the plague.

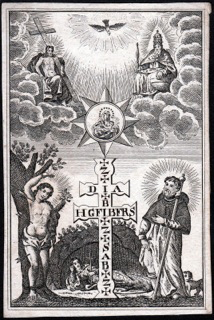

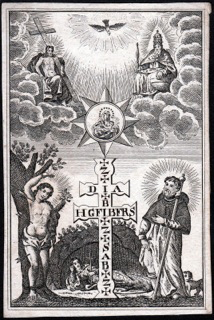

On an interesting engraving dating to the 17th century, three Saints are represented: Saint Sebastian, Saint Rosalia, and Saint Rocco (see image).

On an interesting engraving dating to the 17th century, three Saints are represented: Saint Sebastian, Saint Rosalia, and Saint Rocco (see image).

On the image, around the Cross of Saint Zaccaria, on which are inscribed the “Sacred Letters,” there are the three saints named above, praying to Heaven, where the Virgin appears, and above Her, the Saint Trinity.

Saint Sebastian was considered the most powerful protector against the plague. As we know, he was martyred with several arrows. His wounds, healed by Saint Irene, were compared to the plague’s bubos. Saint Rocco was struck by the plague, from which he recovered thanks to the help of his dog, Reste. Saint Rosalia became part of this cult because she saved the people of Palermo from the 1624 epidemic.

There is one specific reason why prayers directly addressed to God were not considered very effective, and why the intercession of saints was deemed necessary. Physicians could not provide an explanation for the plague. Hence the belief spread that the plague was a sign of God’s anger at the sins of mankind. This explains the presence of the Virgin Mary on the image: who but Mary could move Jesus to compassion and placate God’s anger?

– Biagio Gamba

www.biagiogamba.it

Translated by Mariolina Salvatori

From Biagio Gamba, Esquire

Collector and Scholar of Immaginette, Santini, Small Devotional Images

Gli antidoti “spirituali” contro la peste

Nel Medioevo sterminò quasi metà della popolazione europea. Esplosa inizialmente in Oriente, si diffuse in Europa veicolata dalle navi che dallo scalo di Caffa (Crimea) raggiungevano Costantinopoli (fu la prima città a essere colpita dal morbo) e da lì Genova, con conseguente diffusione nell’Italia centro settentrionale, e Messina, da cui il morbo si estese al resto del Meridione fino a Roma. Ma l’epidemia – com’è noto – colpì l’Europa intera.

I medici dell’epoca si dimostrarono assolutamente inadeguati e del tutto impreparati nell’affrontare questo mostro terrificante. Allora la scienza medica si nutriva di “altre conoscenze”, in particolar modo di Astrologia. In caso di epidemia, per esempio, questi erano i consigli che i medici impartivano:

1. La serenità dello spirito

2. La sobrietà

3. Solo l’uso de’ cibi sani

4. Tenersi lontano dal contagio

5. Indossare delle lane e de’ minerali

6. Avere fiducia nel medico assistente

7. Uso di oggetti esterni

8. Preghiere, onde essere ben assistito

9. Rassegnazione ai divini voleri.

Questi i rimedi ritenuti efficaci in caso di malattie considerate “invincibili”, come la peste o il colera. Accanto a pratiche che, anche oggi, potremmo considerare di una certa validità, come l’uso di cibi sani (3), l’evitare il contatto con individui infetti (4), la fiducia nel medico (6), l’uso di oggetti esterni all’ambiente colpito dalla malattia (7), gli altri consigli erano tutti di natura “spirituale”.

Nel marzo 1547 la peste stava diffondendosi nella città di Trento, allora sede del celebre Concilio. I padri conciliari decisero di sospendere i lavori e di trasferirsi a Bologna. Si racconta che gli stessi si salvarono grazie a un particolare esorcismo, recitando una giaculatoria, già in uso dai tempi del Medioevo.

La formula era stata inserita in una particolare croce, detta Croce di San Zaccaria, Vescovo di Gerusalemme.

La formula era stata inserita in una particolare croce, detta Croce di San Zaccaria, Vescovo di Gerusalemme.

Le lettere, che dovevano ricevere una precisa benedizione, dovevano essere portate addosso (mediante una medaglia, un’immaginetta, una reliquia) con sincera devozione, in tempo di peste. Secondo la leggenda sarebbero state scritte di proprio pugno dallo stesso Santo, su una pergamena, poi ritrovata nel Monastero di Frayles in Spagna.

Evito qui di trascrivere l’intera giaculatoria, piuttosto lunga, che si compone di una serie di invocazioni, ognuna delle quali inizia con una delle lettere trascritte sulla croce. Mi limiterò a riportarne qualcuna.

Crux Christi salva me

Zelus domus tuae liberet me

Crux vincit, Crux regnat, Crux imperat, per signum crucis libera me, Domine, ab hac peste

Deus Deus meus: expelle pestem a me, et a loco isto, et libera me

In manus tuas Domine, commendo spiritum meum, cor, et corpus meum

Ante Caelum, et Terram Deus erat, et Deus potens est liberare me ab ista peste

La (mia) traduzione è la seguente:

Croce di Cristo salvami; Lo zelo per la tua casa mi liberi; La Croce vince, la Croce regna, la Croce governa, attraverso il segno della Croce liberami, o Signore, da questa peste; Dio, Dio mio: caccia la peste via da me, e da questo luogo, e liberami; Nelle tue mani Signore, affido il mio spirito, il cuore, e il mio corpo; Dio era prima del Cielo e della Terra e perciò può Diò liberarmi da questa peste.

Chi abbia composto realmente questa giaculatoria non è dato saperlo. Sono evidenti alcuni riferimenti alle Sacre Scritture e in particolare ai Salmi. In parte, invece, è un esempio di invocazioni a carattere popolare che ritroviamo molto spesso nei riti di natura sincretistica (vedi anche il mio Gli Agathazettel e il rito del fuoco e il mio Quando i devoti mangiavano i santini).

Ma sappiamo benissimo che le preghiere avevano maggiore efficacia se accompagnate dall’intercessione dei Santi. Nel caso specifico, esistevano dei Protettori contro la peste. L’elenco sarebbe lungo: i loro nomi variano anche a seconda dei luoghi di culto.

Facendo riferimento all’immagine rappresentata su una interessante incisione settecentesca, che potete osservare qui sotto, ne menzionerò soltanto tre, in essa raffigurati: San Sebastiano, Santa Rosalia e San Rocco.

Facendo riferimento all’immagine rappresentata su una interessante incisione settecentesca, che potete osservare qui sotto, ne menzionerò soltanto tre, in essa raffigurati: San Sebastiano, Santa Rosalia e San Rocco.

Come potete osservare, attorno alla Croce di San Zaccaria, sulla quale sono inscritte le “Sacrae Litterae” vi sono San Sebastiano, Santa Rosalia e San Rocco, oranti al Cielo, dove appaiono la Vergine e sopra di Lei la Santa Trinità. Un concetrato di potenza si potrebbe dire.

San Sebastiano era considerato il più potente protettore contro la peste. Come sappiamo, egli fu martirizzato con diverse frecce, che gli provocarono molte ferite, curategli da Santa Irene. Tali ferite erano paragonate ai bubboni provocati sulla pelle dalla peste. San Rocco fu egli stesso vittima della peste, dalla quale riuscì a guarire anche grazie all’assitenza del suo fedele cane, di nome Reste. Santa Rosalia si meritò il culto dei Palermitani, che salvò dall’epidemia nel 1624.

C’è un motivo preciso però che spiega perché le preghiere rivolte direttamente a Dio non fossero ritenute molto efficaci e, dunque, era più opportuno rivolgersi agli intercessori. Come si è accennato, gli stessi medici non riuscivano a dare una spiegazione alla malattia, per cui si pensò che essa fosse il risultato dell’ira di Dio che si scatenava sugli uomini per i loro peccati.

Si spiega così anche la presenza, all’interno dell’immaginetta, della Madonna: chi più di Maria poteva commuovere Gesù e placare l’ira di Dio?

– Biagio Gamba

www.biagiogamba.it

Grazie!

Grazie Mariolina per il lavoro che fai di traduzione e divulgazione del lavoro di noi collezionisti. Sei un elemento prezioso per la filiconia.

Curiosi Appellativi Della Madonna

This post on “Curious Appellatives of the Virgin Mary” is my translation and condensed version of a fascinating visual / textual essay published by Patrizia Fontana Roca on her website, www.cartantica.it.

Among the numberless appellatives of the Virgin Mary, records of Her infinite powers, some are indeed “curious.” Their “curiosity,” Patrizia underscores, can be just fortuitous, the result of an artist’s whim, or of a cultural or political situation. Most “curious” images of the Virgin Mary and their titles are self-explanatory. Others less so, and in need of glossing. With Patrizia’s permission I reproduce here an image of Madonna delle Corna (Madonna with Horns), several images of “Madonna del Soccorso,” one of Madonna del Flagello (Madonna of the Scourge), and the relevant information about them Patrizia provides.

Cappella Portinari (Convent of Sant’ Eustorgio, in Milan) houses the earthly remains of San Pietro da Verona, Martyr, as well as a fresco of Mary and Child with horns sprouting from their foreheads! The fresco narrates an extraordinary legend / miracle.

While Saint Peter was celebrating Mass, at the moment of Consecration, trying to tempt him, the devil disguised himself in the form of Mary and Baby Jesus. But in his haste, he forgot to hide his horns.

Saint Peter saw them, and discerning the devil’s ploy, he raised the Host toward him. The devil quickly vanished.

Madonne del Soccorso / Madonnas of Soccour

Before visiting Patrizia’s website, the images of Madonna del Soccorso I was familiar with were the soothing ones of Mary of Perpetual Soccour, loving images of a mother holding her baby who holds onto her thumb. The images of Madonna del Soccorso on Cartantica website startled me, but at the same time, they made me feel fiercely protected, taken care of. Here is Mary taking control of the situation, clubbing away whoever threatens her fold. Recurring, poignant details of these images are Mary’s hand holding a club raised to protect the child who takes refuge under her mantle, and a weeping mother, begging the Virgin to save her child. The iconography of fierce Madonnas, writes Patrizia, was mainly promoted by Agostinian Fathers whose intention was to persuade the faithful of God’s power on the forces of evil, and of the Holy Mother’s divine tutelage of the faithful, especially the young, the simple, and the defenseless.

– Mariolina Salvatori and Patrizia Fontana Roca

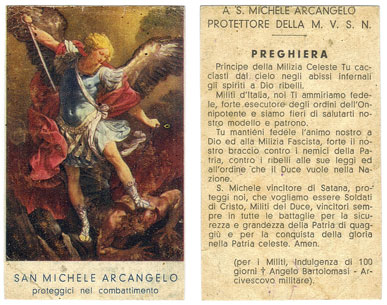

Saint Michael, Protector of …

“I wonder why they always choose him.”

“I wonder why they always choose him.”

This is the question Biagio Gamba poses, tongue in check, about the many and diverse groups of “faithful” who ask for and assign Saint Michael the power to protect them. He points out that Saint Michael is the protector of hosiers, hatters, apothecaries, scale makers, pharmacists, merchants, judges, radiologists, gilders, grocers, parachuters, and state police.

So far, so good. But, Gamba reveals, such polar opposites as Fascist black shirts, Italy’s Partisans, and … members of the Mafia organization ‘Ndrangheta, have also turned to him for protection in their fighting and killing missions. (Apparently ‘Ndrangheta mafiosi burn a Saint Michael image during their oath of affiliation.)

So far, so good. But, Gamba reveals, such polar opposites as Fascist black shirts, Italy’s Partisans, and … members of the Mafia organization ‘Ndrangheta, have also turned to him for protection in their fighting and killing missions. (Apparently ‘Ndrangheta mafiosi burn a Saint Michael image during their oath of affiliation.)

Gamba’s sardonic comment about why Fascists, Partisans, and Mafiosi should all trust in Saint Michael’s help is that He is also the protector of those who dying ask that their souls be saved.

San Michele, Protettore di . . .

I.

Chissà perché scelgono sempre lui. È il protettore dei magliai, dei cappellai, degli speziali, dei costruttori di bilance e degli schermitori, ma anche dei farmacisti, dei commercianti, dei giudici, dei radiologi, dei doratori, dei droghieri, dei paracadutisti e della polizia di stato. È stato anche patrono delle Camicie Nere fasciste e dei Partigiani d’Italia.

Chissà perché scelgono sempre lui. È il protettore dei magliai, dei cappellai, degli speziali, dei costruttori di bilance e degli schermitori, ma anche dei farmacisti, dei commercianti, dei giudici, dei radiologi, dei doratori, dei droghieri, dei paracadutisti e della polizia di stato. È stato anche patrono delle Camicie Nere fasciste e dei Partigiani d’Italia.

Forse non tutti sanno che San Michele Arcangelo è anche il protettore di una delle più importanti organizzazioni criminali italiane e, ormai, del mondo: la ‘Ndrangheta. E pochi sicuramente sanno che durante il rito di iniziazione di un nuovo affiliato alla “famiglia” viene bruciato un santino, raffigurante appunto l’Arcangelo.

Di questo rito ne hanno parlato importanti giornalisti, come Roberto Saviano, ma anche l’attuale Procuratore della Repubblica di Catanzaro, Nicola Gratteri, da anni in prima linea nella lotta contro la ‘Ndrangheta e pertanto grande conoscitore della storia e degli uomini dell’Associazione. Chi voglia approfondire l’argomento può leggere uno dei tanti testi dedicati.

Quello che a me interessa capire è però il motivo per cui San Michele Arcangelo è stato scelto quale protettore di gruppi di uomini, appartenenti a generi di vita diametralmente opposti.

Perché Polizia di Stato e ‘Ndrangheta hanno scelto, probabilmente inconsapevoli l’una dell’altra, di affidarsi allo stesso santo protettore?

Per quanto riguarda i poliziotti, il discorso è piuttosto semplice. San Michele può essere considerato il più importante poliziotto di Dio, colui che è sempre presente nella lotta contro il Maligno. Nei nostri santini lo troviamo raffigurato con la spada o con la lancia mentre trafigge il suo nemico principale, Satana.

Ma l’Arcangelo Michele è anche rappresentato con una bilancia in mano, attributo che rimanda al ruolo di Giudice – ricordiamo che, secondo la tradizione cristiana, San Michele ha il compito di “pesare le anime”, prima del loro Giudizio – baluardo di quella Giustizia Assoluta, rappresentata da Gesù Cristo e dunque da Dio in persona. E proprio in tal senso si comprende il perché il Santo sia stato scelto dai “santisti” (affiliati) della “santa” (la famiglia).

Ma l’Arcangelo Michele è anche rappresentato con una bilancia in mano, attributo che rimanda al ruolo di Giudice – ricordiamo che, secondo la tradizione cristiana, San Michele ha il compito di “pesare le anime”, prima del loro Giudizio – baluardo di quella Giustizia Assoluta, rappresentata da Gesù Cristo e dunque da Dio in persona. E proprio in tal senso si comprende il perché il Santo sia stato scelto dai “santisti” (affiliati) della “santa” (la famiglia).

Non è infatti un caso se il santino raffigurante San Michele venga bruciato durante il giuramento di affiliazione. Il giuramento è un momento importante, sacro appunto. Chi lo rende lo fa a prezzo della sua stessa vita: è un giuramento di sangue (durante il rito, il nuovo fratello poggia la mano sulla punta di un coltello). Dunque, chi aderisce alla Famiglia si obbliga, con il sangue, a rispettare le regole della Famiglia. Testimone di questo giuramento è il Santo Giudice per eccellenza, che partecipa al rito attraverso un santino che, bruciando, trasmette questa testimonianza direttamente in cielo.

II.

Povero San Michele! Non bastava che schermitori, commercianti, speziali,  farmacisti, radiologi, cappellai, magliai, produttori di bilance, doratori, giudici, paracadutisti e poliziotti, lo avessero eletto protettore delle rispettive categorie. Negli anni Trenta del Novecento i fascisti della Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, meglio conosciuti come camicie nere, lo scelsero come loro protettore.

farmacisti, radiologi, cappellai, magliai, produttori di bilance, doratori, giudici, paracadutisti e poliziotti, lo avessero eletto protettore delle rispettive categorie. Negli anni Trenta del Novecento i fascisti della Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, meglio conosciuti come camicie nere, lo scelsero come loro protettore.

Ma da cosa doveva proteggerli? E perché scelsero proprio lui e non un altro santo?

Un santino, stampato intorno agli anni Quaranta, intitolato all’Arcangelo, reca la didascalia: San Michele Arcangelo – proteggici nel combattimento. E certo, da cosa sennò? Sul verso, la preghiera riportata ne chiarisce bene i motivi:

Tu mantieni fedele l’animo nostro a

Dio ed alla Milizia Fascista, forte il no-

stro braccio contro i nemici della Pa-

tria, contro i ribelli alle sue leggi ed

all’ordine che il Duce vuole nella Nazione.

Chiaro no? Il resto della preghiera potete leggerlo direttamente sull’immagine riportata qui sotto.

Naturalmente, l’Arcivescovo militare, Angelo Bartolomaso, concedeva per l’occasione ai Militi fascisti una indulgenza di 100 giorni. Be’, qualche peccatuccio l’avranno pure commesso!

Va detto che le camicie nere non erano un corpo militare, ma dei civili, che volontariamente “difendevano”, con le armi, la Patria e l’Ordine fascista.

Fra il 1943 e il 1945, l’Italia conobbe un’altro corpo di volontari, il cosiddetto Corpo Volontari della Libertà, più noti alla Storia d’Italia e agli italiani, con il nome di Partigiani. Anch’essi non erano dei militari, ma erano ugualmente armati e combattevano contro i fascisti e gli occupanti nazisti. Ebbene, chi pensate che avessero scelto come loro protettore?

San Michele Arcangelo, naturalmente.

Di seguito, uno stralcio della preghiera riportata su un santino di quegli anni, stampato da FB

Noi Partigiani d’Italia, armati per

la difesa della Patria contro il

barbaro invasore nazista e contro

il traditore fascista, da queste vette

inviolate delle Alpi Ti invochiamo

I toni della preghiera “dei garibaldini” sono piuttosto diversi da quelli usati dai fascisti. Tuttavia – consentitemi una considerazione – la sostanza non cambia: uomini che invocano lo stesso santo perché li aiuti a combattere e a uccidere altri uomini. Per fortuna che San Michele Arcangelo fosse anche il protettore dei moribondi: veniva/viene infatti invocato, in punto di morte, perché questi ottengano una “buona morte” andando in Paradiso.

– Biagio Gamba

www.biagiogamba.it

Crowned Madonnas / Madonne Incoronate

Crowned Madonnas / Madonne Incoronate

The coronation of sacred images, of Madonnas in particular, a rite that began around 1500, was performed with special solemn liturgies approved by Capitolo Vaticano. The Benedizionale makes clear that the decision so to honor an image of the Virgin Mary is the responsibility of the diocesan bishop and local community. However such honor is bestowed only on images of the Virgin Mary that have inspired and sustain genuine and widespread devotion. The devotion of Pope Clemens VIII (1592-1605) to the image of Salus Populi Romani, venerated in the Basilica of S. Maria Maggiore, contributed to its coronation.

The coronation of sacred images, of Madonnas in particular, a rite that began around 1500, was performed with special solemn liturgies approved by Capitolo Vaticano. The Benedizionale makes clear that the decision so to honor an image of the Virgin Mary is the responsibility of the diocesan bishop and local community. However such honor is bestowed only on images of the Virgin Mary that have inspired and sustain genuine and widespread devotion. The devotion of Pope Clemens VIII (1592-1605) to the image of Salus Populi Romani, venerated in the Basilica of S. Maria Maggiore, contributed to its coronation.

In 1960, the coronation of the Black Madonna of Oropa followed. This rite, subsequently incorporated in Pontificale Romano, was greatly promoted by Count Alessandro Sforza Piacentini who paid for the coronation of a good number of images, among which Madonna della Vittoria and S. Maria in Portico. (When Baby Jesus was part of the image, he too was crowned.) In Spain, the first images canonically crowned, are the Virgen del Monserrat (Barcelona) and Virgen de los Reyes (Seviglia).

In 1960, the coronation of the Black Madonna of Oropa followed. This rite, subsequently incorporated in Pontificale Romano, was greatly promoted by Count Alessandro Sforza Piacentini who paid for the coronation of a good number of images, among which Madonna della Vittoria and S. Maria in Portico. (When Baby Jesus was part of the image, he too was crowned.) In Spain, the first images canonically crowned, are the Virgen del Monserrat (Barcelona) and Virgen de los Reyes (Seviglia).

– Patrizia Fontana Roca

Translated by Mariolina Salvatori

For a more detailed account of this rite,

and for a stunning gallery of crowned images,

please visit Patrizia’s website @ www.cartantica.it

Madonne Incoronate

Madonne Incoronate

Il rito dell’Incoronazione delle immagini sacre, in particolar modo della Madonna in tutti i suoi appellativi, nacque attorno al 1500, e veniva praticato con solennità e liturgie speciali, dopo l’approvazione del Capitolo Vaticano.

Il Benedizionale, al numero 2034, precisa che “Spetta al vescovo diocesano, insieme con la comunità locale, giudicare sull’opportunità di incoronare l’immagine della beata Vergine Maria. Si tenga tuttavia presente che è opportuno incoronare soltanto quelle immagini che, essendo oggetto di venerazione per la grande fiducia dei fedeli nella Madre del Signore, godono di una certa notorietà, tanto che il luogo in cui son venerate è diventato sede e centro di genuino culto liturgico e di attivo impegno cristiano”.

La devozione di Papa Clemente VIII (1592-1605) per la Salus Populi Romani, presente nella Basilica di S.ta Maria Maggiore, si espresse appunto con l’ incoronazione dell’immagine. Successivamente, nel 1620, venne incoronata la Madonna Nera di Oropa.

La devozione di Papa Clemente VIII (1592-1605) per la Salus Populi Romani, presente nella Basilica di S.ta Maria Maggiore, si espresse appunto con l’ incoronazione dell’immagine. Successivamente, nel 1620, venne incoronata la Madonna Nera di Oropa.

Il rito poi si estese a tutta la chiesa, finendo per incorporarsi al Pontificale Romano, per immagini a cui i fedeli erano molto devoti, a causa a volte di miracoli avvenuti o per la protezione prodigata dalla Vergine in casi di grandi calamità.

Il rito poi si estese a tutta la chiesa, finendo per incorporarsi al Pontificale Romano, per immagini a cui i fedeli erano molto devoti, a causa a volte di miracoli avvenuti o per la protezione prodigata dalla Vergine in casi di grandi calamità.

La spinta maggiore alla pia pratica, fu data dal Conte Alessandro Sforza Piacentini che fece incoronare a sue spese un buon numero d’immagini della Vergine. Tra le prime immagini che beneficiarono di questa pratica, la Madonna della Vittoria, e S. Maria in Portico. Quando era presente accanto alla Madonne, anche il Bambino Gesù veniva incoronato.

In Spagna le prime immagini mariane coronate canonicamente sono state, a Barcellona, la Virgen del Monserrat, e poi a Siviglia la Virgen de los Reyes.

Non di tutte le effigi, purtroppo, si può reperire la data dell’Incoronazione.

– Patrizia Fontana Roca

For a more detailed account of this rite,

and for a stunning gallery of crowned images,

please visit Patrizia’s website @ www.cartantica.it

The Devil on Small Format Images

The Catholic Church has always used images to indoctrinate and catechize its fold. In the Middle Ages, images of the devil, juxtaposed to images of the Guardian Angel, were produced and distributed to frighten sinners about the consequences of their transgressions.

The Catholic Church has always used images to indoctrinate and catechize its fold. In the Middle Ages, images of the devil, juxtaposed to images of the Guardian Angel, were produced and distributed to frighten sinners about the consequences of their transgressions.

Since the IX century, the devil was represented as a small, deformed, old, or large variation of the human body. To indoctrinate the faithful about its tricks, the devil was represented as a seductive libidinous woman, or as a saint, in which case the deception was visualized through bestial details–horns, hoofs, bat wings, goat ears. (See for example, on this site, the post “Curiosi Appellativi della Madonna” for the legend of “Madonna con le Corna / Madonna with Horns.”)

Representations of the devil as an animal or monster were remnants of the pagan imaginary (satyrs, chimeras, harpies, gargoyles) as well as of the medieval imaginary (snakes, dragons, monkeys, lions, wolves, cats, gryphons, centaurs, reptiles). Most animal features had to do with the head (goat horns, pointed ears, wolf, dog or lion muzzles, and bird beaks), the extremities (nails, claws, hooves), and the body (usually represented as hairy or scaly and with a pointed tail). A reminder of its divine origin, the devil sports feather wings, similar to those of angels, and in the XII century, bat wings. An important detail of the devil’s image is a wide open mouth with a protruding tongue. The devil’s colors are dark browns, blues, and greens, and in the Middle Ages, reds, linked to blood and the flames of hell.

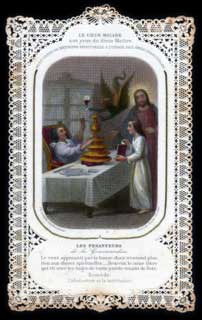

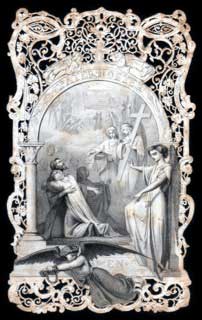

The Devil on Prayer Cards

Modern prayer cards represent the devil as a small, defeated, and humiliated figure—a snake crushed under the Immaculate Conception’s foot, a dragon slained by Saints, or as in the temptation of Saint Anthony, as a winged human figure. On the other hand, representations of the devil on antique prayer cards recall its role in Christian history and philosophy. Here are two examples:

In the first three centuries of Christendom, the fall of Lucifer, the “Morning Star,” was attributed to envy and lust. In the IV century, its fall was attributed to excessive pride.

In this engraving on background decorated with punch-marks (Dopter, Publisher), Lucifer looks like an angel except for his bull horns, his wings, half-way between those of a crow and a bat, and his angered gaze.

The Angel Seducer

In the first book of the Bible, Lucifer, the seducer, convinces Eve to eat and make Adam eat the forbidden fruit. He is the seducer of humanity, which he hates, because it is God’s masterpiece, and upon which he takes vengeance by tempting and corrupting it with lust, riches, and power.

In the first book of the Bible, Lucifer, the seducer, convinces Eve to eat and make Adam eat the forbidden fruit. He is the seducer of humanity, which he hates, because it is God’s masterpiece, and upon which he takes vengeance by tempting and corrupting it with lust, riches, and power.

In this engraving (Durand, Publisher), the devil is represented as he tries to seduce a female figure, identified as Mary, Mother of Jesus.

The devil is insidious and relentless: its left hand offers gold jewels, symbols of riches and power, its right hand tries to shift Her gaze from the Cross to the opposite of heaven.

On the background, on the left, the side that leads to God, nature is lush and bathed in the light of the Cross; on the right, the side the devil points to, nature is sterile, scorched by hell’s fire.

– Gianluca Lo Cicero

Italian Collector and Opera Singer

Translated by Mariolina Salvatori

www.gianlucalocicero.com

Il Diavolo nelle Immagini Devozionali di Piccolo Formato

Premessa

La Chiesa cattolica ha fatto sempre uso delle immagini per indottrinare e catechizzare i fedeli. Per molto tempo nelle immagini che raffiguravano il diavolo prevalse l’aspetto didattico ed ideologico piuttosto che quello estetico.

Il diavolo e conseguentemente il suo carattere maligno e negativo furono rappresentati in modo da impressionare e spaventare i peccatori con la paura dei tormenti infernali; nel medioevo la sua figura associata al male divenne importante ed essenziale nella sua figura in contrapposizione con l’Angelo Custode egualmente presente affiancato all’uomo.

Nell’iconografia cristiana il Diavolo acquisisce importanza solo a partire dal XI secolo in cui esplode la sua presenza nell’iconografia. Gli artisti che si apprestavano a riprodurlo si pongono sempre il problema su come rappresentarlo, dato che non si conosce compiutamente la sua natura e si sceglie di ritrarlo attraverso la diversità e la varietà delle sue metamorfosi che la chiesa e la paura umana gli attribuisce.

Dal IX secolo l’iconografia del diavolo si fondava più sull’aspetto umano assumendo l’aspetto di un essere piccolo e deforme, oppure quello di un vecchio; altrimenti come un essere grande e grosso. Per indottrinare i fedeli sulle astuzie del maligno viene raffigurato anche con l’aspetto di donna seducente e libidinosa, per ingannare un uomo di fede, assume addirittura le sembianze di un santo, anche se nell’immagine l’inganno viene denunciato in genere attraverso un dettaglio in cui la forma umana veniva contaminata associandone caratteri bestiali (zampe o zoccoli, ali di pipistrello, orecchie caprine).

Le rappresentazioni animalesche o mostruose erano eredi dell’immaginario pagano (i satiri, le chimere, le arpie o le gorgoni) e successivamente di quello medievale e quasi sempre richiamavano in qualche modo il serpente (l’ingannatore dei progenitori Adamo ed Eva) e il drago (Apocalisse su tutti ma anche in altri passi biblici e di tradizione cristiana), la scimmia, il leone, il caprone, il lupo, il gatto, il grifone, il centauro, i rettili.

Le caratteristiche animali si concentrano perlopiù sulla testa (corna caprine, orecchie appuntite, muso di lupo, di cane, di leone o becco d’uccello) e sull’estremità delle membra (unghie, artigli o zoccoli), mentre il corpo è peloso o ricoperto di scaglie e provvisto di coda con estremità appuntita. Per rievocare la sua origine angelica il diavolo (nell’Alto medioevo) viene dotato di ali piumate, identiche a quelle degli angeli, mentre dal XII secolo, inizia ad essere raffigurato con ali di pipistrello.

Contrariamente agli angeli, il diavolo è generalmente rappresentato nudo (carattere negativo) e il loro atteggiamento espressivo è improntato sulla tensione, l’agitazione, l’aggressività; la postura curva e contorta che esprime lo sgraziato gesticolare; le forme appuntite delle corna e delle altre estremità (capelli, criniera ma anche denti e peli e il naso adunco, particolare, quest’ultimo, connesso allo stereotipo razziale degli ebrei al fine di demonizzarli) o le pieghe e le grinze, vengono contrapposte alle armoniose vesti degli Angeli e dei Santi.

Particolare importanza riveste la bocca nell’immagine demoniaca; essa è generalmente spalancata e con la fuoriuscita della lingua a formare un ghigno animalesco.

L’uso del colore contribuisce a esprimere la natura del diavolo e senza dubbio le sfumature scure sono le principali caratteristiche del diavolo, il nero, anche se rappresentante l’assoluta mancanza di luce è raramente utilizzato nel cromatismo demoniaco; vengono utilizzate altre tinte per accentuare la sua natura infima e l’appartenenza al mondo delle tenebre, viene usato il bruno, il blu scuro, il verde scuro e da qualsiasi altro colore scuro e saturo. Solo nel tardo medioevo il colore rosso divenne diabolico, associato al sangue e alle fiamme infernali.

L’uso del colore contribuisce a esprimere la natura del diavolo e senza dubbio le sfumature scure sono le principali caratteristiche del diavolo, il nero, anche se rappresentante l’assoluta mancanza di luce è raramente utilizzato nel cromatismo demoniaco; vengono utilizzate altre tinte per accentuare la sua natura infima e l’appartenenza al mondo delle tenebre, viene usato il bruno, il blu scuro, il verde scuro e da qualsiasi altro colore scuro e saturo. Solo nel tardo medioevo il colore rosso divenne diabolico, associato al sangue e alle fiamme infernali.

Riassumendo, l’iconografia del diavolo si evolve da una non-rappresentazione a una raffigurazione che sottolinea sempre più il carattere negativo, carattere che viene enfatizzato contrapponendolo al lato negativo di Dio, di Gesù Cristo, di Maria, degli angeli e dei santi, sempre in una posizione subordinata o comunque sconfitto.

Il diavolo nei santini

Nei santini moderni la sua raffigurazione è poco presente se non come minuscola presenza in alcune iconografie che lo ritraggono sconfitto ed umiliato: come serpente ai piedi dell’Immacolata concezione, come drago ucciso dai Santi, Domenica, Marta, Giorgio etc. e come figura umana con ali di pipistrello mentre tenta S. Antonio.

Nei santini antichi però è possibile vederlo rappresentato con alcune caratteristiche che ne descrivono il ruolo nella storia e filosofia cristiana.

Ne abbiamo scelte due.

L’angelo caduto

Nei primi tre secoli dell’era cristiana veniva attribuita all’invidia ed alla lussuria, la caduta di Lucifero (o Stella del Mattino), mentre a partire dal IV secolo iniziò a divulgarsi la credenza che il principale motivo della cacciata dal paradiso era da attribuirsi solo alla superbia.

In questa siderografia su fondo trinato a punzone edita dalla casa editrice parigina Dopter la figura di Lucifero (già fuori dall’immagine del paradiso) è molto simile a quella di un angelo, e si diversifica in pochi dettagli, le corna taurine e le ali che sono in una fase intermedia tra quelle piumate di un corvo e quelle di un pipistrello, mentre il suo sguardo è truce e incattivito dalle catene che gli cingono i polsi.

In questa siderografia su fondo trinato a punzone edita dalla casa editrice parigina Dopter la figura di Lucifero (già fuori dall’immagine del paradiso) è molto simile a quella di un angelo, e si diversifica in pochi dettagli, le corna taurine e le ali che sono in una fase intermedia tra quelle piumate di un corvo e quelle di un pipistrello, mentre il suo sguardo è truce e incattivito dalle catene che gli cingono i polsi.

L’angelo seduttore

Fin dal primo libro della Bibbia la figura di Lucifero si rivela per quel che è, un seduttore. E’ colui che convince Eva a mangiare e far mangiare ad Adamo il frutto proibito da Dio, è il seduttore dell’umanità, che disprezza, poiché essa e tutta la creazione è il capolavoro di Dio, e su di essa si vendica tentando di traviarla per rivoltarla contro il suo stesso creatore e lo fa servendosi delle sue debolezze, la lussuria, la ricchezza, il potere, con cui tenta e lusinga.

In questa siderografia su fondo trinato a punzone, edita dalla casa parigina Durand, il diavolo è raffigurato mentre tenta di sedurre una figura femminile che è ovviamente identificata in Maria, madre di Gesù.

In questa siderografia su fondo trinato a punzone, edita dalla casa parigina Durand, il diavolo è raffigurato mentre tenta di sedurre una figura femminile che è ovviamente identificata in Maria, madre di Gesù.

Il diavolo è insidioso e il suo stare a contatto con il corpo di Maria è indice di insistenza, con la mano sinistra offre dei monili d’oro che simboleggiano la ricchezza e il potere ad essa conseguenziale, mentre con la mano destra cerca di distogliere lo sguardo dalla Croce, indicando la parte opposta del cielo.

Anche la natura che fa da sfondo è diversificata, sul lato sinistro che va verso Dio, la natura è rigogliosa ed illuminata dai raggi che partono dalla Croce in alto, mentre nella parte opposta che precede il diavolo e da esso indicata è una natura sterile ed arsa dalle fiamme infernali che lambiscono il terreno.

– Gianluca Lo Cicero

Italian Collector and Opera Singer

www.gianlucalocicero.com

From Rosemary Cappello,

Italian American Poet and Artist

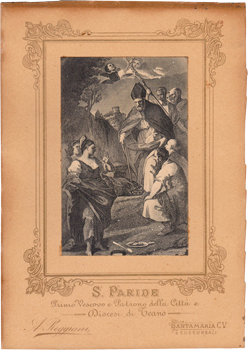

THE ETCHING OF SAN PARIDE

When my grandmother and my father

When my grandmother and my father

came to America,

they brought along an etching of

San Paride.

He was the patron saint of their town,

Teano, Italy.

Every August 5th,

when Dad announced “Today is

the feast of San Paride,”

we prepared to celebrate.

I can still see the sacrificial

eggplant as Mother

(Grandmother had retired from the kitchen)

prepared the meal,

slicing the eggplant into

wafer-thin slivers which were

fried crisp, drained

and placed in tomato gravy flavored

with grated parmesan and sweet basil.

An August day in Llanerch was hot as

an August day in Teano.

After Dad set up the fan in the

kitchen near Mother, he went to the State Store

a couple miles away

to buy wine, a white handkerchief

tied around his neck to catch his sweat.

He walked instead of driving his

bedraggled car.

Finally, we feasted, savoring that

delicious food, Grandmother widening her

eyes and saying, with an appreciative nod

in the direction of Mother, the cook,

“Ah! Saporita!”

All of us, including me, the youngest,

were giddy from wine, but not too giddy

to catch an occasional sigh from Grandmother

or to see her cast a glance toward that

etching she had carried over rough, wartime waters,

that detailed work of art,

that etching of San Paride that has

quietly outlived them all.

– Rosemary Cappello

From Paul Kameen,

America Poet, Writer, Teacher

Lapis Lazuli

I grew up in a large family in a small town. Everyone knew everyone else and people we knew died regularly. My mother was Irish, so going to wakes and funerals was just a part of everyday life, and we were indoctrinated into that culture from a young age. One of the conventions of those occasions was the prayer card, which any attendee could pick up near the door. These had an image on the front—Jesus or a saint, say—a prayer on the back, along with the name of the deceased. I never wondered, until just now, how they got those cards printed so fast. But they were always there. I used to have a small stack of them, mostly relatives, but they disappeared somewhere along the way. These were not necessarily somber events, except for the immediate family of the deceased, of course, but produced a sense of elevation, where the quotidian affairs of “life” in this world seemed suddenly to be superficial, even irrelevant, where time slowed down dramatically, almost didn’t move, a liminal space not entirely of this world or next. I will not say I enjoyed them, but I always felt as if I was learning something about what was of real value in this life.

Later on, I became an altar boy, a very reliable one, so for years I got called to serve almost every funeral in our church, dozens of them. I would get to be excused from school for a few hours to do this. I had the same experience at those occasions. All of the noisome grieving, especially at grave-side, that had nothing directly to do with me would prod my consciousness into this other dimension where I would stay for maybe an hour or so thereafter. I would come back to school and think how shallow and misguided, sometimes even rude and stupid, were the ongoing transactions of everyday life. People had such great in-built value. I had just seen the evidence of that from those left behind after their loss. Why couldn’t everyone see that every second of every day? Why would we treat each other so badly, or just blandly? That state of consciousness would diminish quickly and I would return to normal life, partaking I’m sure, quite shortly, in the same shallow, misguided, rude and stupid behaviors that afflict us at ground level in this world.

My wife’s sudden passing last year seems to have lifted me, and left me, in that state semi-permanently now, a neither-here-nor-there-ness that I experience, strangely, as freedom, able still to participate in all things this-worldly, but without taking them very seriously, maybe like that “serving-man” with “a musical instrument” “carved in Lapis Lazuli,” in Yeats’ great poem, climbing with his two Chinese brethren towards “the little half-way house,” seated now to rest:

There, on the mountain and the sky,

On all the tragic scene they stare.

One asks for mournful melodies;

Accomplished fingers begin to play.

Their eyes mid many wrinkles, their eyes,

Their ancient, glittering eyes, are gay.

– Paul Kameen

www.paulkameen.com

From Maria Famá,

Italian (Sicilian) American Poet

THE BLACK MADONNA OF TINDARI

The Black Madonna of Tindari in Sicily took gentle

vengeance on a woman who came on a pilgrimage, her

baby in her arms.

On climbing the shrine’s wind swept cliff, the woman

exclaimed

“I traveled so far to see somebody blacker than me!”

In an instant, her child disappeared

transported to a spot of dry sand below

in the midst of the Mediterranean Sea

the woman screamed, a boat was sent to rescue her child

she realized that

The Black Madonna of Tindari taught

that racism is a sin.

– Maria Famá

From Maria Terrone,

American Poet and Writer

Faith

In the church vestibule I pass

the monitor that registers the bodies

of the faithful as gray

flickers, a second of ash

on a screen, and heave against the doors.

At 3 p.m. no one else is here but saints,

corporeal in their sandals and robes,

carrying staffs, books, painted bouquets,

their kind faces cracking

as if they too know

how it feels to come apart.

Wedged into the fingers of St. Jude

is a hand-printed prayer, a paper bud

curled so tight, I feel its plea

for a miracle tug the back of my throat:

cure the cancer, kick the habit–the ineffable

longing of a stranger’s words alive

on my own tongue.

Days later, the hand holds instead

a shriveling rose stem.

Petals lie scattered about

like small, white-robed monks,

backs arched to heaven,

faces pressing stone.

– Maria Terrone

www.mariaterrone.com

La Iglesia de la Asunción in Navarette

Hola,

Hola,

For your collection: We found this ex-voto (1713) in La Iglesia de la Asunción in Navarette (a pueblo in La Rioja, on the Camino de Santiago). It was a large (4’ x 3’) framed painting. It reminded us of the ones we had seen in Ecuador.

This one was commissioned by Don Manuel Joseph de Bernabeitia y Coloma, a Caballero in the order of Santiago, to thank the virgin for the miracle that saved him during a storm at sea. Bernabeitia (who died in 1726) served in Mexico City (and most likely suffered the storm on his return), so he was certainly aware of the tradition of the Mexican ex-voto. His son stayed in Mexico and achieved fame as a poet.

– Dave and Joyce Bartholomae

From Maria Famá,

Italian (Sicilian) American Poet

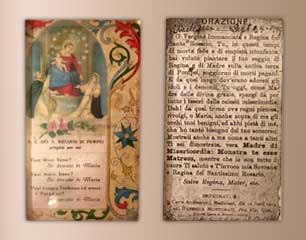

Dear Mariolina, Al Tacconelli urged me to write to you about my father’s experience of a holy card during WWII on the frontline in France. My father’s name was Rosario and he was devoted to La Madonna del Rosario, sometimes called La Madonna di Pompeii.

In 1939, my father left Sicily for the USA when his father called his sons to America where he’d become a citizen. My grandmother and aunt remained in Sicily all through the war. Still learning English, my father was drafted into the army and was in the Normandy invasion. My father had met my mother, Francesca Guaetta, when he was taken to visit other paesani here in Philadelphia, They married in 1948.

My mother, still a teenager in high school, wrote to my father all through the war as did her own mother, Domenica Bongiovanni Guaetta. In September 1944, my father’s onomastico on October 7 was approaching and my mother was writing to him. Her mother gave her a holy card of La Madonna del Rosario that she, herself, had gotten as a child in school and told my mother to include it in the letter to my father. The prayer on the back was in Italian.

When the letter arrived on the frontlines in France, at Metz, on the border with Germany, my father opened the letter, put my mother’s letter in his pocket to savor later and began to read the prayer to the Blessed Mother on the back of the image. He was in a foxhole with another soldier, Cassidy. As soon as he finished the prayer, he put it in his shirt pocket and heard a voice telling him to get out of the foxhole, which one is never supposed to do. He obeyed the voice. He grabbed Cassidy and they ran out of the foxhole.

Within seconds a bomb hit the site where he had been reading the prayer destroying everything including all his gear. He would have been killed if he had remained. My father always told this story crediting La Madonna for saving his life. He kept the holy card all through the war. When he returned, he framed it and it hung in our dining room as proof of the miracle. Now that my parents are deceased, I have the holy card in its frame hanging in my dining room. It remains as a testament to the miracle granted my father by Our Lady of the Rosary.

Within seconds a bomb hit the site where he had been reading the prayer destroying everything including all his gear. He would have been killed if he had remained. My father always told this story crediting La Madonna for saving his life. He kept the holy card all through the war. When he returned, he framed it and it hung in our dining room as proof of the miracle. Now that my parents are deceased, I have the holy card in its frame hanging in my dining room. It remains as a testament to the miracle granted my father by Our Lady of the Rosary.

– Maria Famá

From Al Tacconelli,

Italian American Poet and Painter

The role of immaginette in my life began when I was young. I remember seeing holy cards tucked on picture frames––pictures of angels stomping on the fiery heads of sinners, Saint Rita receiving the stigmata, Asian babies being baptized by angels and missionary nuns, and all the others which I’ve forgotten. These holy cards have been lost over time, but I still have three cards; the one just mentioned about Asian babies, and Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception––printed 1911 in Italy. These managed to survive. I have them tucked in a special book beside my bed. I feel comforted knowing they were handled by my mother and grandmother.

In the movie Moon Struck there is a great line––an Italian American character says to an American man; “I know what I come from.” These words ring true for me in the decades since childhood. Many times I saw Nonna kneeing at the foot of her bed praying Stations of the Cross from an old worn booklet with wonderful illustrations, and the small table in her bedroom crowded with painted plaster saints, and red votive candle burning. And of course, Nonna’s and Ma’s constant rosaries. I used to help Nonna cross the street so she could visit Sa’Rose to say prayers together.

I feel blessed to have the small tarnished crucifix from one of Nonna’s rosaries, and from Nonno’s casket a crucifix engraved with Tomaso Tacconelli 1957, and perched on top of the doorbell fixture in the dining room a chipped plaster Infant of Prague with a penny under his feet in order that I stay solvent. They provide a sense of belonging to something in the distant past which continues through me. The key is to remember, as I do in some poems. They live in these poems and a part of me lives too.

Nonna’s Rosaries

| Rosaries, endless recitation of rosaries, earnest prayers for whom, for what–– were they answered ever. From one of your broken rosaries I kept a small tarnished silver crucifix, its corpus worn smooth from fingered prayers. Perhaps they were answered, was it countless rosaries that protected me in my yet unfurled future. | As a child, to your gratitude’s amazement, I threaded needles mending rips and holes in hand-me-down clothes. Dear Nonna, we are becoming forgotten, soon I must bid farewell to loves whose loveliness is my undoing––will your faithful rosaries guide me across eternity to be with those who’ve rejected me, will my shameful follies be at last forgiven. |

Holy Cards

| 1. Tucked inside the birthday card, cousins Joe and Liz sent today, a saccharine holy card––plastic laminated Saint Joseph cradling in his arms the Child Jesus. | 2. They came one day, not elite Knights of Columbus, but two smooth talking Masons promising more business, more money, success if my father became one of their members. Grease stained hands opened the ornate National Cash Register, pulled out a holy card, Saint Joseph, patron saint of workers, and then my father said, “This is my religion.” |

– Al Tacconelli

From the Road

From Dave Bartholomae, Theorist and Scholar of Composition Studies

and Joyce Bartholomae, Professor (and Lover) of (Anything) Spanish

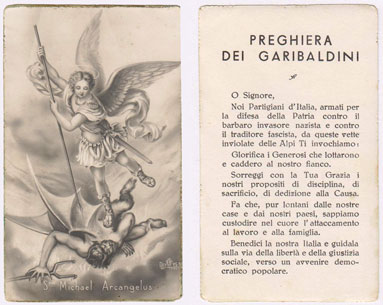

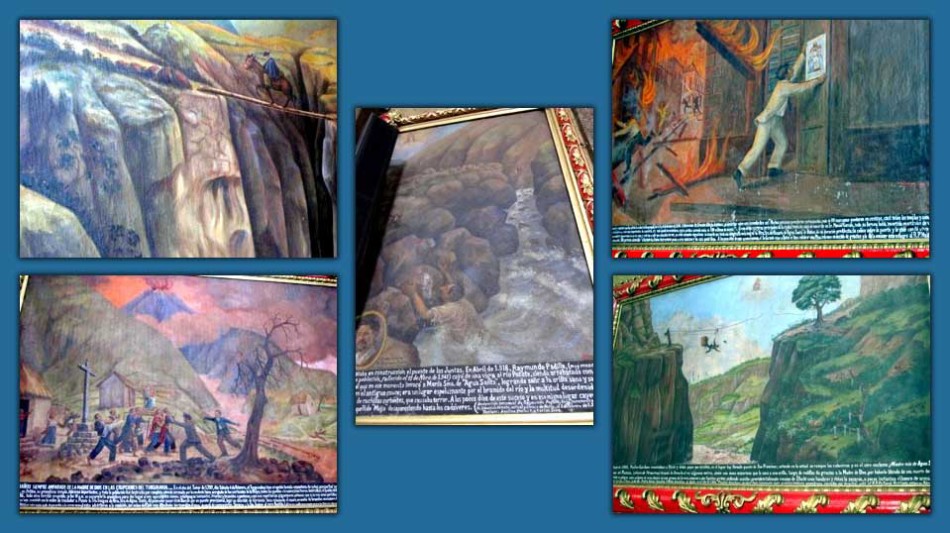

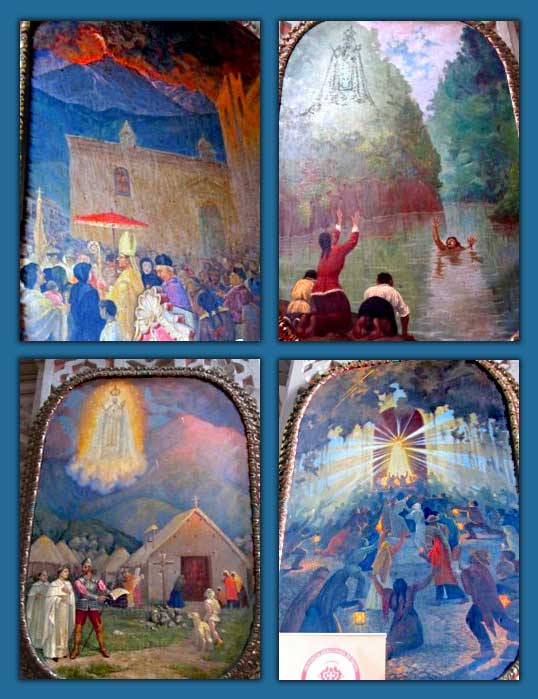

This first of these images comes from a small church in Banos, a mountain town. The story we heard is that these were originally painted on the walls by different artists, then in the 30s some hired a painter to copy / replace them all in a single size and style. You’ll see that the miracles feature bridge building, volcanoes and floods.

This second series comes from the Basilica de la Merced. The Mercedarios was the order that had the power during the period of independence. Unfortunately, the photos don’t show the captions—all very short.

They tell the stories of appearances of the Virgin, all at key moments in the history of Ecuador—from the conquistadores, to the founding of the city, to independence and during periods of epidemic, volcanoes and earthquakes. These were also from the 30s.

– Dave and Joyce Bartholomae